Behind-the-scenes look at “André Kertész: Postcards from Paris”

We had funding from several sources. We are always grateful to our funders, who help turn our ambitions into reality, and we always thank them wherever we can. You can see the list of individuals and foundations who helped support the exhibition and book in the acknowledgments pages of the catalogue, the exhibition credits on the title wall of the show, and on our website.

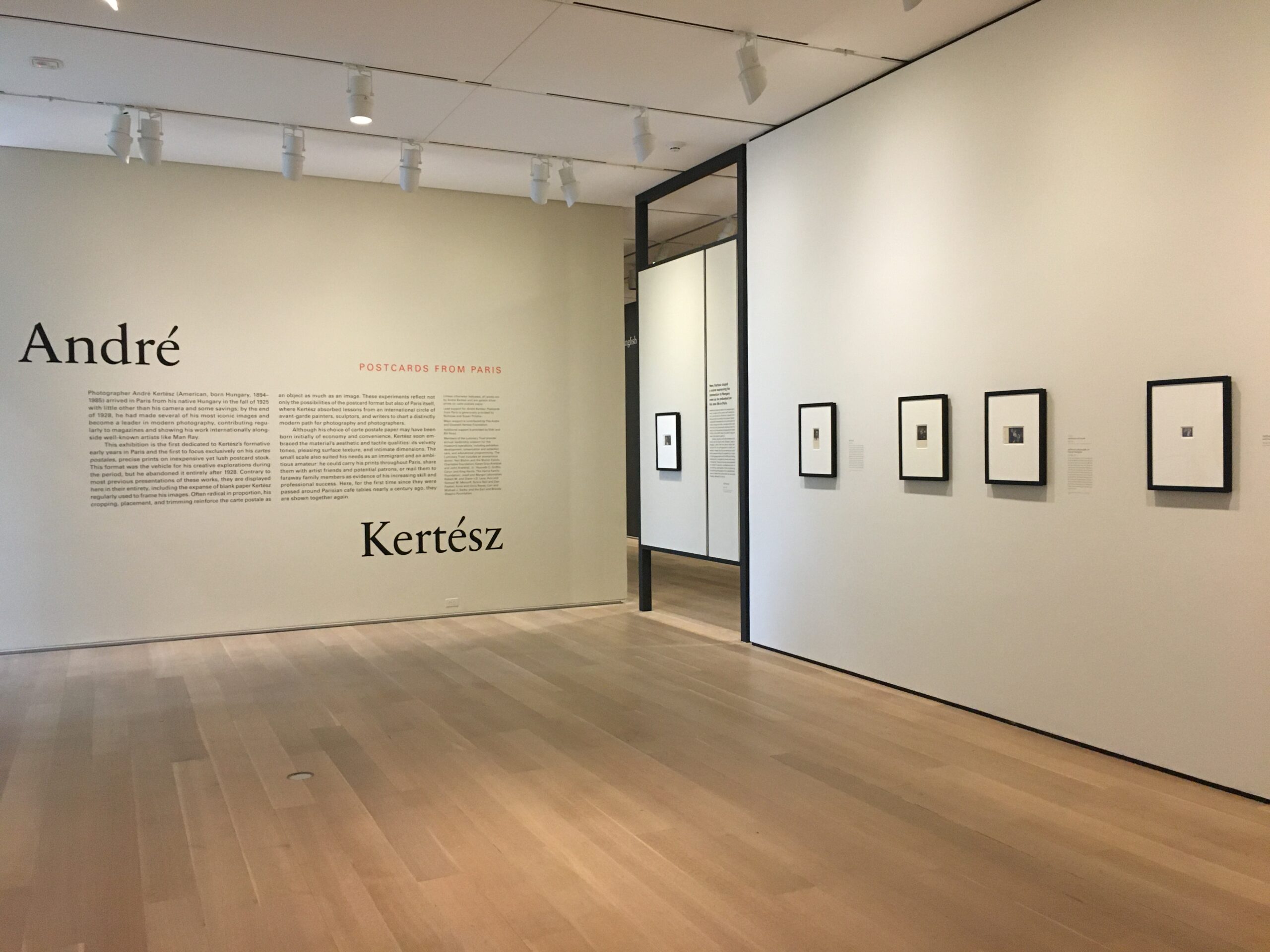

Our designer, Samantha Grassi, worked with me over Zoom to iterate several designs (she is a whiz with changing things in the software on the fly). What we ended up with was a design that really speaks to the blank and negative spaces of the paper and the individuality of the photographic object, all in a beautiful setting for viewing. We had one bang-up, four-hour design session in which we laid out every single object in the exhibition. After that, there were small tweaks but we basically got it. If only I could be that productive in other areas of my life!

Our designer, Samantha Grassi, worked with me over Zoom to iterate several designs (she is a whiz with changing things in the software on the fly). What we ended up with was a design that really speaks to the blank and negative spaces of the paper and the individuality of the photographic object, all in a beautiful setting for viewing. We had one bang-up, four-hour design session in which we laid out every single object in the exhibition. After that, there were small tweaks but we basically got it. If only I could be that productive in other areas of my life!

André Kertész

Photographer André Kertész (American, born Hungary, 1894–1985) arrived in Paris in the fall of 1925 with little more than a camera and some savings.

By the end of 1928, he was contributing regularly to magazines and exhibiting his work internationally alongside well-known artists like Man Ray and Berenice Abbott. The three years between his arrival in Paris and his emergence as a major figure in modern art photography marked a period of dedicated experimentation and exploration for Kertész. During this time he carved out a photographic practice that allowed him to move between the realms of amateur and professional, photojournalist and avant-garde artist, diarist and documentarian.

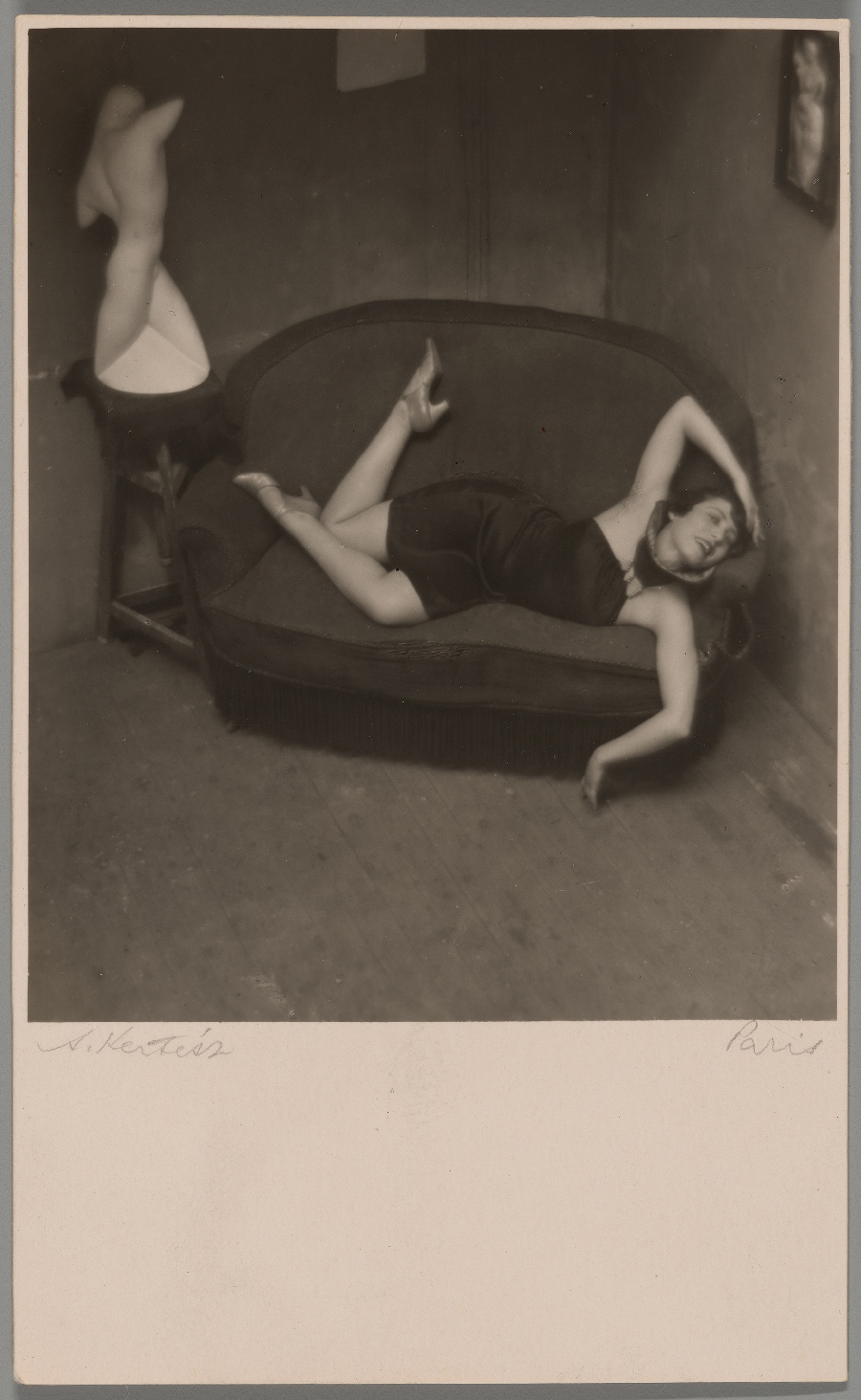

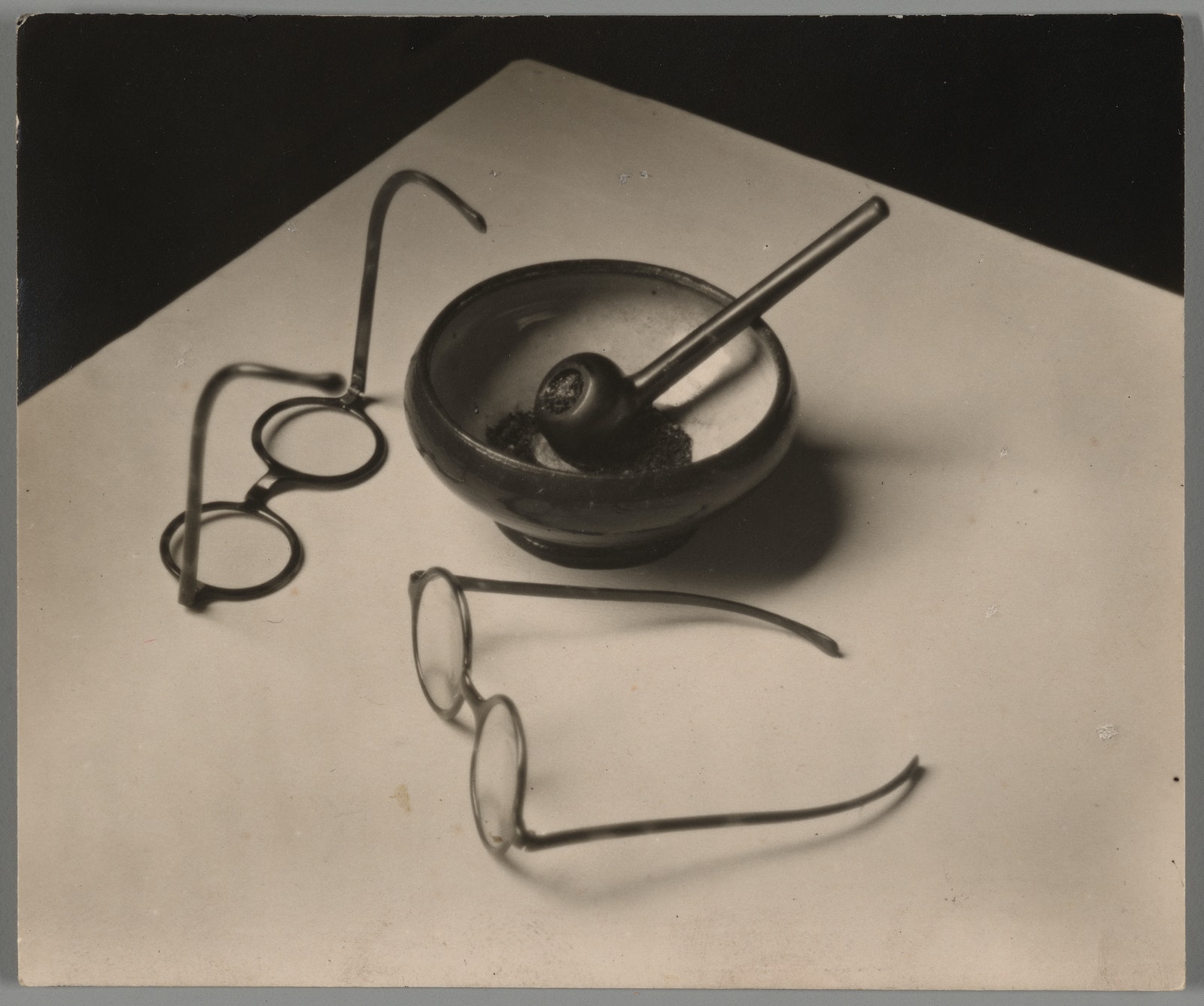

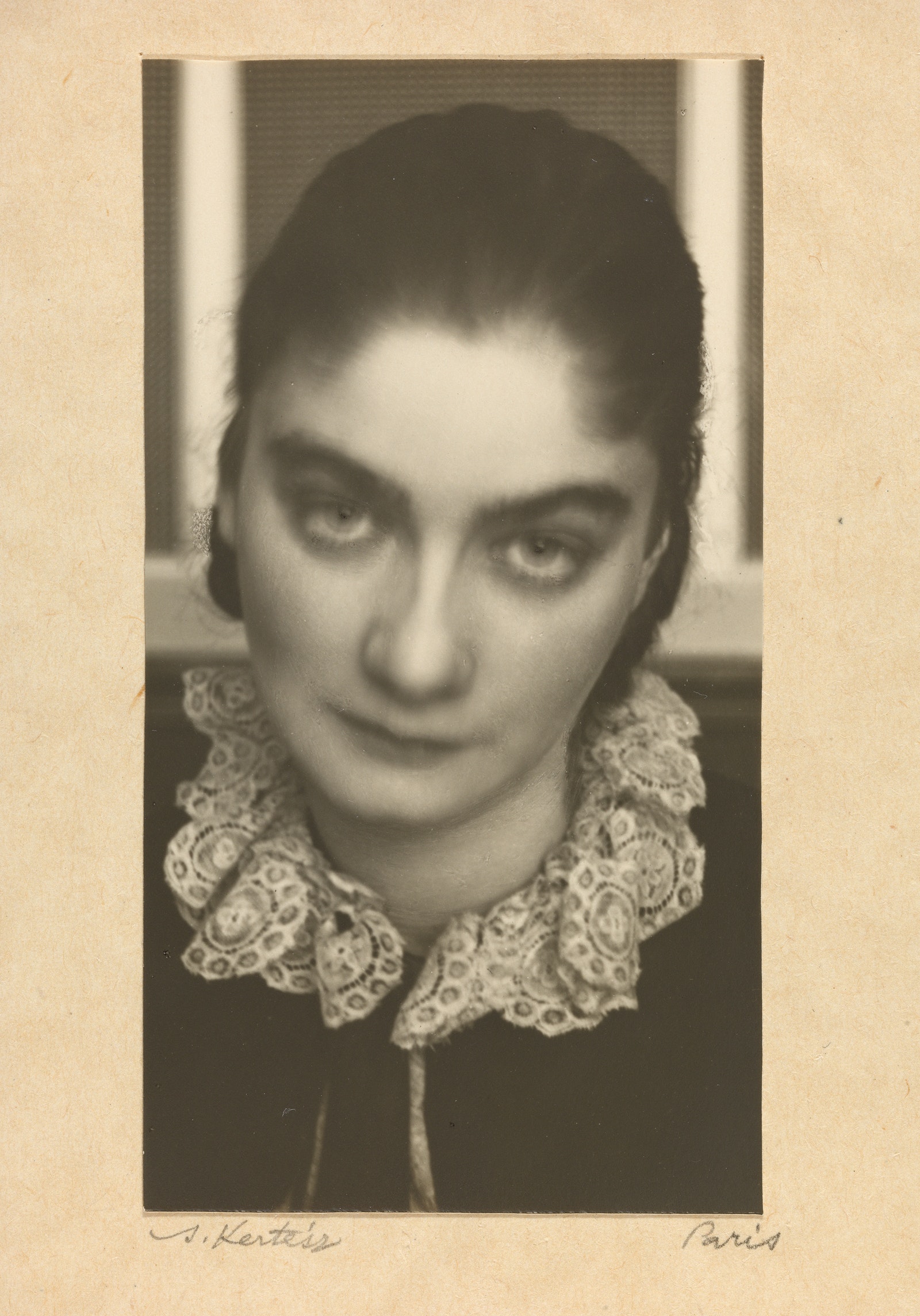

For those three years only, Kertész produced most of his prints on carte postale, or postcard, paper. Although his choice may have initially been born of economy and convenience, he turned this popular format toward artistic ends, rigorously composing new images in the darkroom and making a new kind of photographic object. The small scale of the cards also allowed them to circulate in a way befitting an immigrant artist—shared with a widening circle of international friends at the café table or sent in an envelope to faraway family.

André Kertész. Satiric Dancer, 1927. Family Holdings of Nicholas and Susan Pritzker. © Estate of André Kertész 2021

André Kertész. Mondrian’s Pipe and Glasses, 1926. Family Holdings of Nicholas and Susan Pritzker. © Estate of André Kertész 2021.

André Kertész. Hilda Daus, 1927. Private collection, courtesy Corkin Gallery, Toronto. © Estate of André Kertész 2021.

André Kertész: Postcards from Paris

Oct 2, 2021 – Jan 17, 2022

Art Institute of Chicago

Chicago, IL