“Picture Gallery of the Soul” Exhibit at the Katherine Nash Gallery at the University of Minnesota.

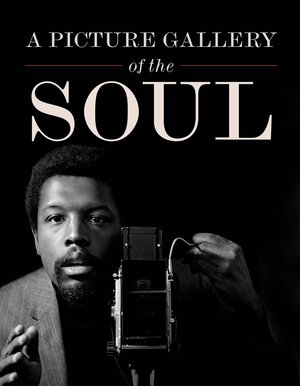

A Picture Gallery of the Soul, is a group exhibition of over 100 Black American artists whose practice incorporates the photographic medium. Sampling a range of photographic expressions from traditional photography to mixed media and conceptual art and spanning a timeframe that includes the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries, the exhibition honors, celebrates, investigates, and interprets Black history, culture, and politics in the United States.

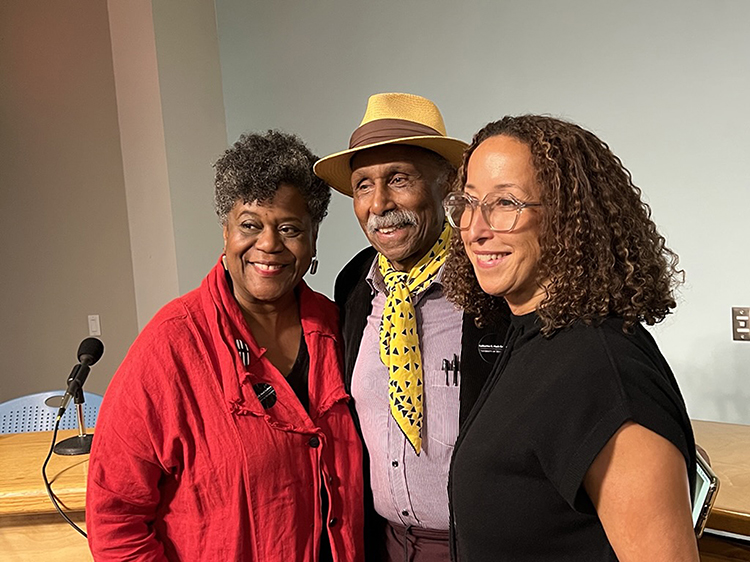

Curatorial Team

Herman J. Milligan, Jr. and Howard Oransky started working on this exhibit in 2016. We asked Howard Oransky, the Director of the Katherine E. Nash Gallery, if he would share the background story of the exhibit and some of the special challenges they faced. His answers are below.

Background

In 2016 I contacted my colleague Herman J. Milligan, Jr. and invited him to join the project with me as co-curator. Herman is a collector and curator of photography, with a special interest in Black photographers. He is President of the Givens Foundation for African American Literature. In addition to his work co-curating the exhibition and organizing the related events, Herman also curated a Soundscape comprised of over 100 musical selections, each one chosen in relationship to a specific image in the exhibition catalogue. It is a massive undertaking. You can listen to the Soundscape on the headphones in the center of the gallery, and we published the Soundscape playlist as part of the gallery guide, which is free and available to the gallery visitors.

How did the idea for the exhibit start?

In January 2014 I received an email from Jim Gubernick, who is an artist and the Facilities Manager at the Regis Center for Art at the University of Minnesota. The Regis Center for Art is home to the Department of Art and the Katherine E. Nash Gallery. Jim suggested that we should present an exhibition of the work of Louis Draper, who taught photography at Mercer Community College in New Jersey where Jim was a student in the 1980s. I had never heard of Louis Draper. At the time I was co-curating an exhibition of Ana Mendieta’s films with Lynn Lukkas. On one of my trips to New York for that project, I saw an exhibition of Draper’s work at the Steven Kasher Gallery. It was amazing. I asked the gallery director if she would loan some work by Draper for a group exhibition of Black American photographers at the University of Minnesota and she agreed. I then began the checklist for the exhibition with one name: Louis Draper.

From that point forward my work on the exhibition became a wonderful process of learning about Black American photographers. When I was on staff at Walker Art Center, I helped the great curator Kellie Jones with her 1995 Dawoud Bey Portraits touring exhibition. I knew about some of the more famous Black photographers like Bey, Gordon Parks, Lorna Simpson, James Van Der Zee, Carrie Mae Weems, and so on. But my knowledge was superficial, and I was totally ignorant of the long history of Black American photographers going back to the inception of photography. I had no idea that Frederick Douglass was the most photographed American of the 19th century. He gave four lectures on photography during the Civil War. I brought those lectures with me on the plane to Sweden when we installed the Ana Mendieta films exhibition at the Bildmuseet in 2017 and I read and reread them on the plane. The title of our exhibition comes from his Lecture on Pictures delivered in Boston in 1861.

Going back to Louis Draper for a moment, I learned that he was instrumental in the founding of the Kamoinge Workshop in New York in 1963. The Kamoinge Workshop was a collective of great Black American photographers, who also later initiated the Black Photographers Annual in 1973. Our exhibition includes work by some of the original Workshop members, including Anthony Barboza, Adger Cowans, Louis Draper, Al Fennar, Herb Robinson, Ming Smith, and Shawn Walker, as well as some other artists who joined the organization later including Salimah Ali, Lola Flash, Russell Frederick, and John Pinderhughes. We also have the first issue of the Black Photographers Annual in the exhibition. The great curator Sarah Eckhardt organized the 2020 touring exhibition Working Together: Louis Draper and the Kamoinge Workshop and the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts has all four issues of the Black Photographers Annual digitized and accessible on their website.

How did the pandemic affect the mounting of the exhibit?

Like many things in life, there was both a positive effect and a negative effect. On the negative side, we had to postpone the exhibition twice, from 2020 to 2021 and from 2021 to 2022. This was disruptive and made it difficult to proceed in an orderly fashion with the fundraising, the loans of artworks, and so on. However, on the positive side it gave me more time to work on the research side of the project which added to the depth and breadth of the curation, and it also provided more time for me to raise the money needed to publish the catalogue and finally negotiate a publication agreement with University of California Press.

Can you explain the process the university goes through to assemble the photos that will ultimately be in the exhibit?

It is a long and winding road! Herman and I would do our research, meet, review and combine our lists of artists, then go back and try and arrange the loans. We borrowed artworks directly from the artists, from museums, galleries, library, and archival collections. Some artists sent us prints which we framed. Some artists sent us digital files which we printed in the Department of Art, then framed. Galleries and museums typically sent the artworks to us already framed, but not always. There are 184 works in the exhibition by 111 artists and for each one of those artists there is a story about how we were able to include their work in the exhibition and catalogue. The owner of the artwork may or may not also be the owner of the copyright, so obtaining copyright holder permissions to reproduce the artworks in the catalogue is a whole other requirement that proceeds alongside the curation. Organizing an exhibition, the catalogue, and the related events is a long, laborious, detail-driven process. The only way to get through it is if you love the artworks. For Herman and me, it was a labor of love, from the very beginning to the very end.

It's also important to mention that we are not working in a vacuum. Just as artists try to move their individual vision forward while learning from the artists who preceded them, as curators we are adding our brick to a road that came before us. Earlier I mentioned Kellie Jones and Sarah Eckhardt. I would also like to acknowledge the foundational contributions made to the field by Deborah Willis. She is University Professor and Chair of the Department of Photography & Imaging at the Tisch School of the Arts at New York University. I first learned about her work as a photographer and in 2016 I invited her to participate in the exhibition. Then, I began to learn about her scholarship, which is immense. Over the last 40 years she has published over 20 books and articles and curated numerous exhibitions on the history of Black American photography. A Picture Gallery of the Soul rests on the edifice of her monumental scholarship. Our exhibition includes her 2020 photographic installation Women’s work never praised, never done that honors Black women’s domestic labor and their political labor to secure and defend the right to vote. Our exhibition catalogue includes an essay she wrote. And on September 15 she presented a dialogic response to our exhibition in an online program.

It takes a village to produce a project of this ambition. Tells us about that.

It most certainly does, and I am deeply grateful for the help we have received over the years of preparation. A team of undergraduate and graduate students in the Department of Art helped with research, printing, framing and installation. Most recently and most intensively, Dez Bilges and Eleanore McKenzie Stevenson worked all summer installing the exhibition. They were led in this effort by our Assistant Curator Teréz Iacovino, who assisted with every aspect of the project and produced the playback system for the Soundscape in the gallery. We had funding from several sources. We are always grateful to our funders. You can see the list of individuals, foundations, and businesses who helped support the exhibition and book in the acknowledgments pages of the catalogue and on our website.

Can you talk about the exhibition catalog?

The Katherine E. Nash Gallery co-published the exhibition catalog with the University of California Press. A Picture Gallery of the Soul includes an image, caption, artist statement and artist biography for each of the 100+ artists in the exhibition, as well as essays by Cheryl Finley, Crystal Am Nelson, Seph Rodney, Deborah Willis and the co-curators. The book can be ordered directly from UC Press or from the University of Minnesota Bookstore. Within the first week of its release our catalogue was ranked as the #1 New Release in Art History on Amazon.

A Picture Gallery of the Soul

September 13 - December 10, 2022

Katherine Nash Gallery

University of Minnesota